|

For over 40 years, conventional wisdom has been that saturated fat causes heart disease and should be avoided or reduced. The targets for reduction have gone progressively down over that time from < 10% to the American Heart Association’s current 5-7% recommendations. During this time, the cardiovascular disease rate (CVD) has decreased to approximately 1/3 of their 1960's levels. While there are many factors (decline in smoking, better control of hypertension, use of statin drugs, and the timely use of blood thinners in acute myocardial infarctions), some cardiologists point to this decline as proof that the nutritional recommendations made in the late 1970s to reduce fat intake and specifically target saturated fat are a big part of this success. More recently, prominent experts have begun to challenge this. "Is saturated fat bad for you?" remains one of the most contentious and confusing questions in medicine today. To answer this question we need to understand the background of what has become known as "The Diet-Heart Hypothesis". In the 1960s, several observations were combined to form the diet-heart hypothesis, which stated: Lowering cholesterol by replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) from vegetable oil would:

This hypothesis, which has been the dominant paradigm for cardiology over the past 40 years, was based on:

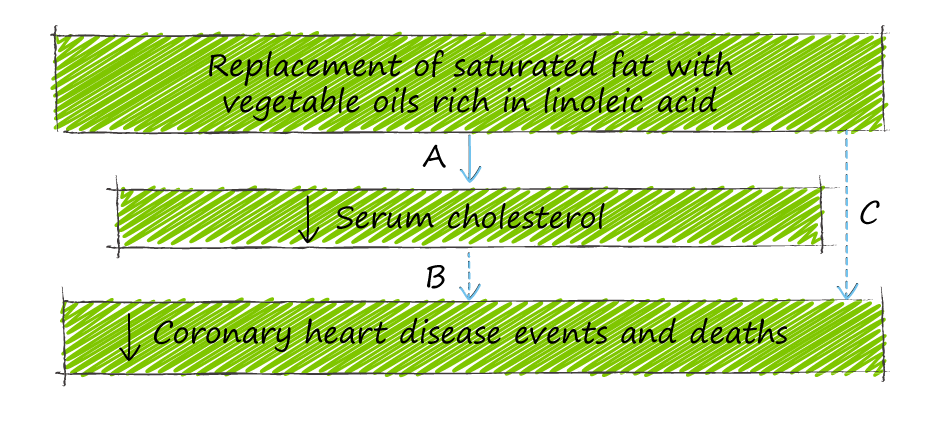

The logic of the diet:heart hypothesis:

The problem with the Diet:Heart hypothesis is that there has been no solid evidence to support the logical leap (A--->C) The original evidence supporting the notion that decreasing saturated fat lowers coronary artery disease came from epidemiological studies in the 1960s that demonstrated a positive correlation between national levels of dietary fat consumption, specifically saturated fat, and heart disease mortality. The most famous (or infamous) study was performed by the legendary Ancel Keyes and was called the "7 Country Study".

Keyes’ study was observational, based on low-quality data: food diaries and public health records on the cause of death. It also was not originally based on “7 countries” - Keyes actually reviewed 22 countries - and when one examines the data from all countries, the correlation, while present, is far weaker. Keyes has been accused of cherry-picking the data to make the correlative conclusion stronger. By today's standards, the “7 Country Study” would be considered deeply flawed, and recent observational studies have shown different results. In 2017, the PURE study, a large 18 country epidemiological cohort study that followed 135,335 people for an average of 7.4 years, demonstrated that high carbohydrate intake was associated with a higher risk of total mortality, whereas total fat and saturated fat intake were related to lower total mortality. Specifically, saturated fat intake was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, or cardiovascular disease mortality and was associated with a decreased risk of stroke. Of course, the challenge with observational studies is that they can show correlation at best. But correlation is not causation - my favourite example is the number of bathrooms in your home correlates with your net worth - the higher one's net worth, the more bathrooms. If we confuse correlation with causation, we could erroneously conclude that having more bathrooms leads to higher net worth and could advocate that individuals should build themselves new bathrooms to increase their wealth! The gold standard for proving causation is the randomized controlled study. No randomized controlled study has shown that replacement of saturated fat with vegetable oil significantly reduces coronary heart disease or mortality. One randomized controlled study that attempted to test the causal role of saturated fat in heart disease was the Minnesota Coronary Experiment (MCE). Conducted from 1968 - 1973, MCE was the largest (9570 people) and most rigorously executed trial of the diet-heart hypothesis and the only dietary study ever to include post-mortem assessment of coronary, aortic and cerebrovascular atherosclerosis grade and infarct status. The MCE followed over 9000 institutionalized people living in state mental institutions and nursing homes, randomly assigning them to two groups. One group maintained the standard diet high in saturated fat. In contrast, the other group had half of the calories from saturated fat replaced with vegetable oil and corn oil margarine - high in the Omega 6 PUFA linoleic acid. Unlike observational studies, the MCE had detailed records of every meal administered to these subjects over 56 months. This study probably could never be repeated as today's ethics boards would disapprove of experimenting on institutionalized patients without consent. So what were the findings? In keeping with the first part of the diet-heart hypothesis - replacing saturated fat with linoleic acid did lower cholesterol by an average of 14%. Interestingly, this lowering of cholesterol DID NOT result in people living longer. In fact, the lower the cholesterol, the higher the rate of death (22% for every 0.75 mmol/L) and the vegetable oil group did not have fewer heart attacks or fewer atherosclerotic plaques. So the MCE, the most rigorous trial ever done to test the diet-heart hypothesis, essentially disproved the notion that decreasing saturated fat improves cardiovascular outcomes – it even suggested that increasing vegetable oil was associated with greater mortality. If this rigorous study was finished in 1973 and essentially disproved the diet-heart hypothesis, why did it not change the prevailing wisdom that saturated fat was bad? It did not change minds because it was never published! The investigators led by Ivan Frantz did not publish because the results were not what they expected, and they felt that something must have been wrong with their data. When part of the study was published years later, in 1989, it only reported that the substitution of saturated fats with vegetable oils did not reduce the risk of heart disease or death. It was not until 2017 that the complete data was analyzed and the true results were presented. Assisting the lead investigator Christopher Ramsden was Ivan Frantz’s son Robert (a prominent Mayo clinic physician himself), who had found old computer tapes and documents in his father’s basement. Ivan Frantz died in 2009. The account of this discovery was the subject of a brilliant Malcolm Gladwell podcast, “The Basement Tapes” Ramsden et al. showed that when the whole data set was thoroughly reviewed, the MCE study results counter the diet-heart hypothesis and show that the replacement of saturated fat with vegetable oil increases coronary events and death. While this was the first full reporting from the MCE trial, a 2013 re-analysis of another 1960’s era landmark study – the Sydney Diet Heart Study (again by Ramsden) also showed that volunteers who replaced much of their saturated fat with polyunsaturated fats high in linoleic acid had a higher risk of death from heart disease. In 2014, Chowdrury et al. reported a meta-analysis of 78 studies involving 650,000 people and concluded that there was no evidence that lowering saturated fat and increasing polyunsaturated fat intake decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease. A landmark 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies showed no association between saturated fat consumption and:

These studies, in many ways, disprove the diet-heart hypothesis as overly simplistic. On the whole, this brings us to the answer to our question: Is saturated fat bad for you? The overall evidence from these studies says probably not – but the true answer lies in your own response to saturated fats.

To learn more about heart disease: To understand your own risk for heart disease, book a Comprehensive Lifestyle Medicine Assessment. |

AuthorDr. Brendan Byrne Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed