|

The EAT Better Strategy:

When we eat food - it is broken down into 3 macronutrients:

When we eat proteins, they are broken down into amino acids - essentially the building blocks for new proteins. These amino acids are absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed around the body to tissues that need them. Dietary protein is predominantly used by our bodies for structure and function and not for fuel. The most important functional molecules of the body - hormones, neurotransmitters, enzymes and antibodies are proteins, as are our structural components - muscle, collagen, connective tissue, and even cartilage and bone. Our bodies need 20 amino acids to be able to create all the proteins that we need for life. Of these 9 are considered to be essential - meaning that we need to get them from our diets.

The body is very good at reutilizing amino acids, but is not fully efficient as some amino acids get damage and broken down. As a result, we always need a to eat some new protein just to maintain our existing proteins. Unlike fats and carbohydrates, we cannot store excess protein, so we are also dependent on our diets to provide enough protein for any growth and maintenance. Excess dietary protein, beyond levels required to restore amino acid balance, are degraded, the amino groups are broken down and excreted as urea, creatinine, uric acid or other nitrogenous metabolites. The remaining carbon skeleton which are keto acids are either utilized as fuel in the liver or converted into glucose or more likely fat. That’s right - excess protein will be turned into fat! This may seem surprising given the popularity of high protein diets for weight loss, but there are two other attributes of protein that may explain their benefit in a weight loss diet. First, of the macronutrients, protein is the most satiating. Meals with high protein feel more filling and decrease hunger for a longer period of time, and a result you will consume fewer calories overall. The other attribute of protein metabolism that helps with weight management is the fact that the process to convert protein into fat is inefficient and about a third of the energy in the protein is consumed in the process. A small percentage of protein is used to maintain blood glucose levels during fasted states. This process, gluconeogenesis, runs at a fairly constant rate throughout the day using multiple substrates including lactate (released from muscle glycogen) and glycerol (from fat breakdown). The amount of protein required for this is very small. Summary

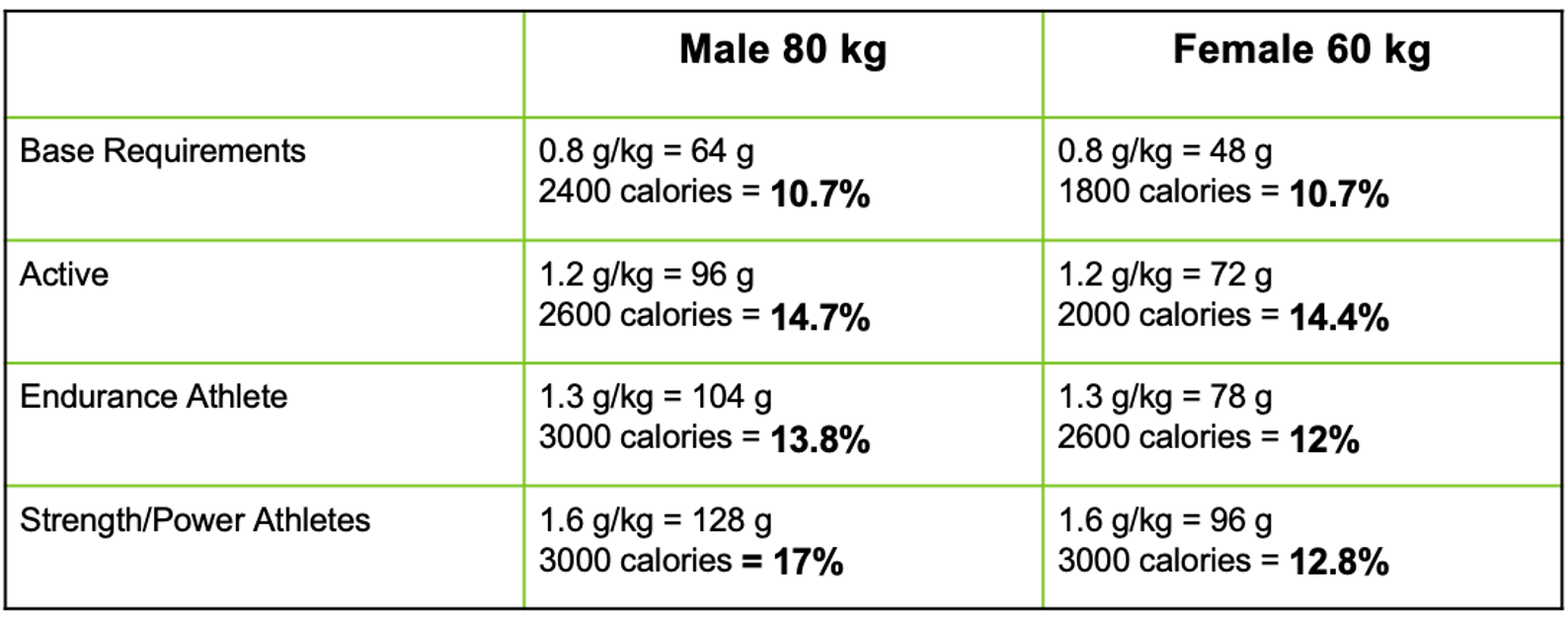

How much protein do we need a day? The official answers from the Institute of Medicine are

0.8 g/kg is meant to be the minimum amount of protein we require without becoming deficient. This is the amount of extra protein our body needs for repair and maintenance or as we discussed above the amount of protein that is lost each day as we recycle our amino acids. As we are more active we need more protein - however the best evidence we have is that these requirements are still rather modest - with up to 1.6g/kg for strength/power athletes who are training to gain muscle mass. There is no evidence that we need beyond 2 g/kg per day. From these examples you can see that based on functional requirements the range of protein intake that we need is between 10-17% of our total calories. The average Canadian intake of protein is 17% Bottom Line: most people get enough protein. One interesting observation about how our bodies regulate protein comes from nutritional studies where subjects are allowed to eat as much food as they want. Overall, people tend towards overconsumption of fat or carbohydrates - especially if these come in refined and processed foods without fibre. When it comes to protein, most people will maintain a consistent protein intake of between 15-20% of their calorie consumption. So while our brains can struggle to regulate fat and carbohydrate intake well, we do self regulate on protein. The simple rule that can be taken from this observation is that when it comes to protein - listen to your body. If you feel like you need protein then be sure to increase your lean protein intake. Are there benefits to having more protein? As we have reviewed, extra dietary protein above and beyond our maintenance, growth and repair will predominantly get converted to fat. While this conversion consumes 33% of the caloric energy, if your overall caloric intake is excessive, you are still increasing your fat by consuming too much protein. The extra protein may however increase your satiation and result in the overall consumption of fewer calories in which case it will support weight loss or maintenance. One time where extra protein may be beneficial is your first meal of the day: break your fast with a meal containing at least 20-30 g of protein. This will signal your body that you have nutrients, increasing metabolic rate and will decrease ghrelin (your hunger hormone). If you are consuming more calories from protein than you require you must be careful and consider the package that comes with the protein - what fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients come along with protein? Eat protein that is low in saturated fat and processed carbohydrates and rich in many nutrients. Is there harm from eating too much protein? For many years, medical textbooks would caution against the harms of too much protein. Specifically the harmful effect of excessive nitrogen excretion from the kidneys. This harm was overstated - as a result the Institute of Medicine guidelines of 10 - 35%. From a longevity standpoint, there is a line of research from Dr. Valter Luongo suggests that high protein consumption is associated with higher rates of cancer, and diseases associated with inflammation. He specifically recommends that adults under age 65 consume no more than 0.7 g/kg and increase to 1 g/kg after age 65. What about protein for older adults? After age 50, we lose muscle mass through a process called sarcopenia, and as our muscle mass decreases we have less internal protein to recycle so the portion that we require from our diets increases. To help prevent, or at least decrease the rate of sarcopenia, the RDA for adults over 50 years is 1 g/kg. Most older adults easily reach this target, and for them the other key to maintaining muscle mass is resistance training. Regular exercise doing body weight exercises or weights has been shown to be the most effective strategy for sarcopenia. If you are like me these answers are hard to translate into our daily lives - what does this mean in terms of actual foods that I am going to eat? Are there differences in protein quality between plants and animal sources? Advocates of eating meat are quick to point out that animal sources are “complete” proteins, meaning that they contain all essential amino acids and fully meet protein requirements gram for gram. The problem with this line of thinking is that plants contain the same 20 amino acids, the origin of the amino acids in animals is originally from plants. Given that both animal and plant proteins are broken down into amino acids before absorption, there is NO fundamental difference between eating meat and eating a variety of vegetable sources of protein. (For more on this read Chana Davis’s excellent blog post: Busting the Myth of Incomplete Plant-Based Proteins. One factor in favour of plant protein over meat is that the plant packages have more micronutrients and fibre without the potentially harmful saturated fats found in meat. What about protein powder? The thing to ask yourself is why? Why are you taking protein powder instead of choosing a healthy whole food protein package? If it is to make your smoothie a satiating substitute for a meal that makes sense. If it is to get more protein into your body it is probably unnecessary. Remember that if you are consuming more calories than you need, that protein powder will get turned into fat! If you are going to choose a protein powder, the advice from Precision Nutrition is pretty good: Stick to the basics.

Summary

(That’s it - it really is that easy) Next - Add veggies, fruits, legumes, whole grains - (7 Reasons Why & 12 Tips How) As I have written elsewhere on this blog, cardio-respiratory fitness (V02Max) and muscle strength are both independent and powerful predictors of longevity. Ruiz and colleagues carried out the most comprehensive study examining the influence of muscle strength and cardiorespiratory fitness on healthy aging. They found that for those over 60, both all-cause and cancer mortality is twice as likely in individuals with low compared to high skeletal muscle strength, and irrespective of strength, low cardio-respiratory fitness is associated with twice the incidence of all cause mortality. Aging is characterized by a decline in the capacity of the body’s major organs, in particular the loss of muscle (sarcopenia) and loss of bone (osteopenia) have severe consequences on the quality of life as we age. From a metabolic perspective, a healthy muscle mass with frequent exercise provides a sink for glucose, making it easier to maintain blood sugars and avoid insulin resistance. The decline of healthy, functional, skeletal muscle, correspondingly is one of the major factors leading to insulin resistance, with higher levels of insulin causing inappropriate fat deposition throughout the body further compromising organ function. Quite separate from the metabolic effects of diminished muscle mass, the loss of functional endurance, strength and range of motion effects locomotory function, compromises balance, increases risk of falls and fractures and leads to diminished health span. Given the clear benefits of muscle strength on healthy aging one key question is what should you do to preserve muscle mass, strength and function across lifespan? There is clear evidence that the trajectory of sarcopenia and muscle loss is highly dependant on activity - in other words exercise dramatically diminishes the loss of muscle associated with age. Repeated resistance exercise results in increased muscle mass by stimulating protein synthesis within the muscle. With aging there is evidence that there is some anabolic resistance to the effect of exercise but that this can be overcome if a sufficient stimulus is maintained. Protein is the essential macronutrient in the diet for the maintenance of muscle strength, mass and function. The current RDA for protein intake to meet whole-body metabolic demands has been stet at 0.8g/kg/day - but this guideline does not differentiate between young and old or between individuals looking to gain or maintain muscle mass. As with many things nutrition related, these one-size fits all metrics don’t make much sense. A better way to think about protein intake, is that they should be optimized to levels that promote maintenance of muscle mass throughout the lifespan. An interesting recent review looked much more closely at this question of how much protein is optimal if you are trying to gain muscle. This meta analysis found that weight lifting regardless of protein supplementation led to strength gains, but for those who increased their protein strength was increased by about 10% and muscle mass by about 25%. When looking for the optimal amount of protein, the sweet spot seems to be around 1.6 mg/kg/day - or roughly twice the RDA. Above this level there was no additional advantage. Interestingly this review did not find any advantage to the type or timing of the protein intake. This may be because the underlying studies were very small, as there is basic science support for the notion that the muscle’s anabolic response to amino acids is maximal in the post workout period and that branded chain amino acids (BCAA’s), in particular leucine are the most potent stimulators of anabolism through the mTOR pathway. Here's the bottom line:

While I won’t get in too much detail here, I would like to point out that when it comes to macronutrient levels there is no simple formula that fits everyone - in fact this is something that needs to be adjusted to each person’s unique genetics, environment and behaviours. For proteins, we have just seen that the optimal level of protein needs to be adjusted to the level of anabolism - more muscle mass increase requires more protein, maintenance less, and under no circumstances do we want the dietary intake of protein to trigger catabolism or muscle breakdown. So we need to define protein intake by the person’s goals - maintenance or anabolism - and adjust accordingly. Dietary proteins that are not used for the body’s protein repair, maintenance and increase of muscle mass, are generally excreted and not used for energy provision. In many ways, our protein rule is to find the minimum level of protein that meets our goals - maintenance or anabolism. For carbs the task is reversed, we should titrate the maximal amount of carbs that we can tolerate while maintaining low and flat blood sugars without any sign of insulin resistance. For people that are already showing insulin resistance, this level will be very low - hence the low carb approach for metabolic disease. For others, (healthy cross-fitters for example), burning lots of calories in metabolically healthy muscles the amount will be higher. And that brings us to fat, the calories that we do not get from carbs to meet our daily requirements must come from fat. Our energy requirements must be met by our intake of fats and carbs. So it you have insulin resistance and are carb intolerant, your fat intake must increase. For today, I will leave it here, but add one last comment, the most important thing to remember about anything related to nutrition is that the source of any of your calories should be coming from nutrient dense whole foods that are not processed or refined. |

AuthorDr. Brendan Byrne Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed